(This is part 2 of the “Stages of the Anthropocene, Revisited” Series (SotA-R).)

Of all climate-change-related disasters, drought may very well be the worst.1 While other kinds of disasters might look more disastrous because of the clearly visible damage they cause, droughts destroys livelihoods. Drought is associated with water shortages (obviously), crop failures, famine, migration/refugees, and violent conflict (including civil war and war). Furthermore, droughts tend to affect larger areas, and the effects are, therefore, widespread. Persistent drought can make once fertile and pleasant lands inhospitable or even uninhabitable. For these reasons, significant changes in global precipitation patterns can have major geopolitical consequence, and those in turn may make some CO₂-emission scenarios unlikely and others more likely.

Unfortunately, there isn’t perfect agreement between predictions of drought or drought risk and their effects, but that is only to be expected, of course. Making predictions is hard, and different models solve various difficulties in different ways. I’m not a climate scientist and I lack the qualifications to judge which models are more and which are less reliable, so the best thing I can do is to combine them. Below you’ll find several maps resulting from this “combination”, but before I’ll show you these maps, I must first explain how they were made.

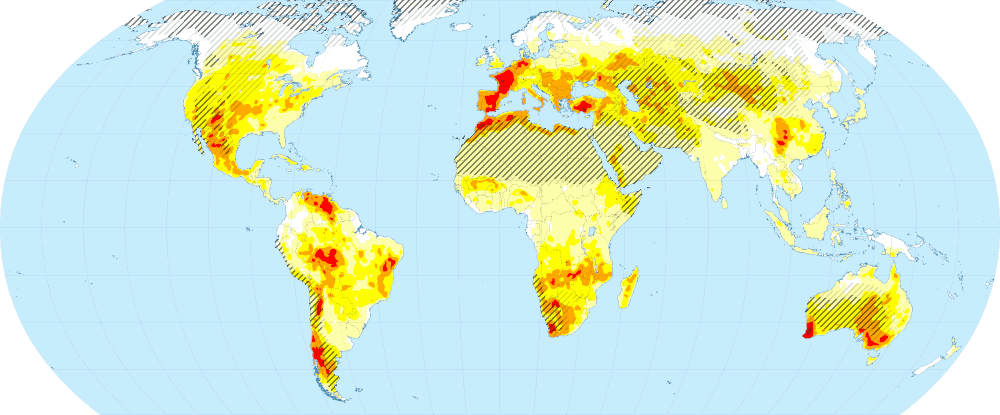

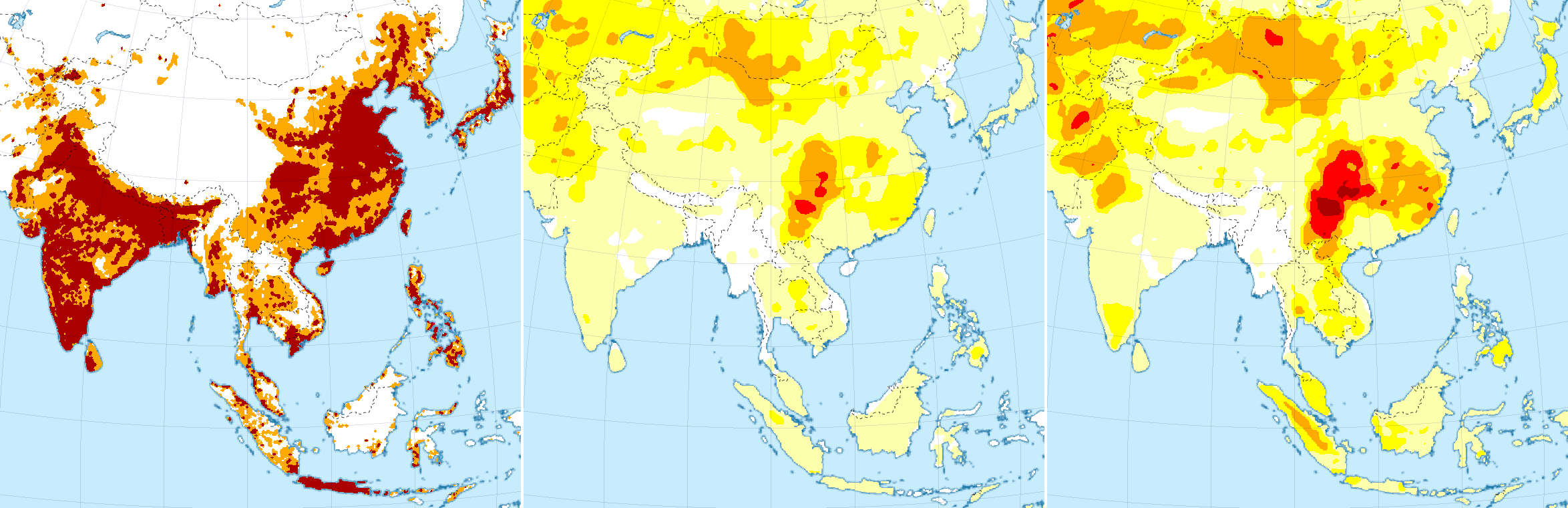

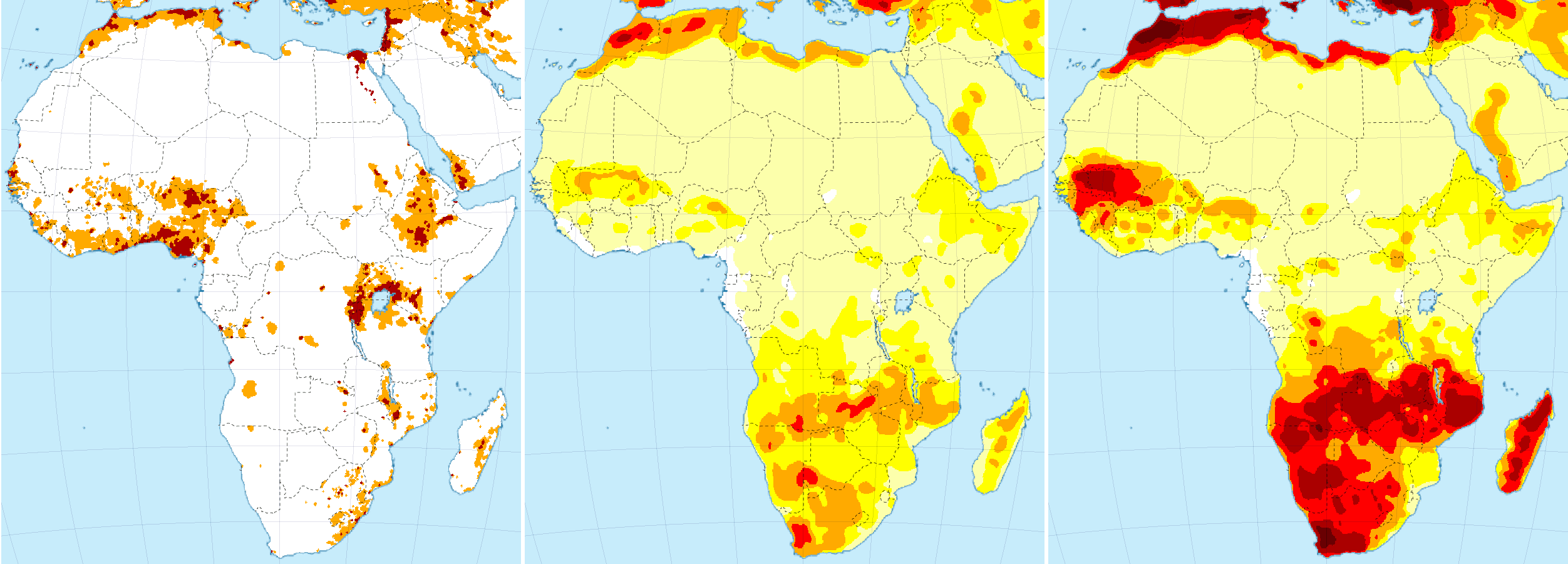

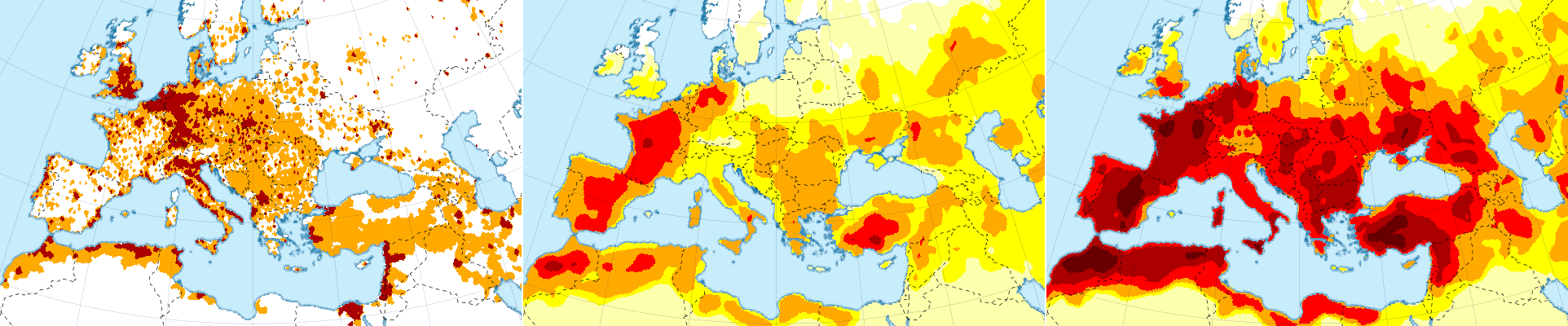

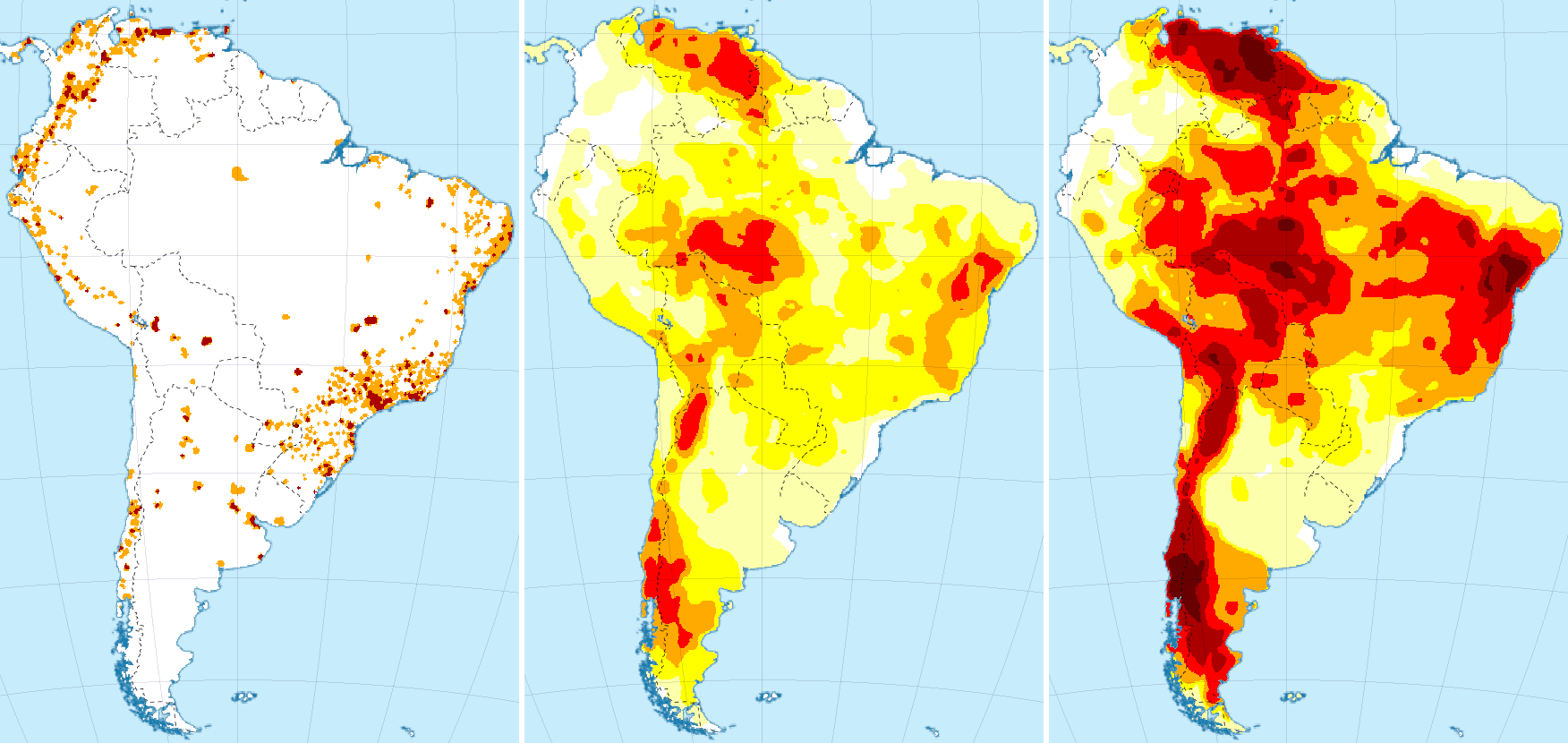

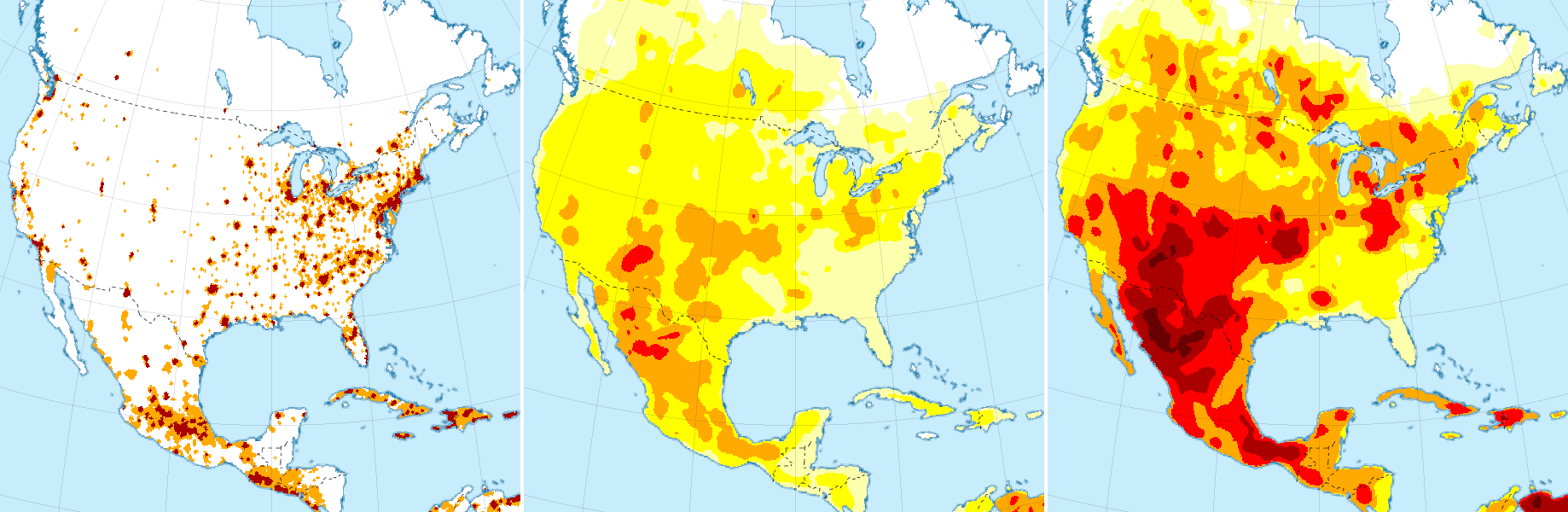

The data sources for the maps in this article are maps of expected drought or drought risk at various points in time or in various conditions included in a number of scientific papers published on the topic in 2018. (That’s not on purpose, by the way, but it turned out that all usable recent papers on the topic that I found were published in that year.) Those maps were converted to the same map projections and then redrawn in identical (changeable) color schemes. After that, they were combined in such a way that the darker an area in the greater number of maps, the darker the area in the combined map. Consequently, dark areas in the combined maps aren’t just areas that are expected to be drier at a given point in time, because different source maps used represent different kinds of data. Rather, the darker an area on a combination map, the drier it is expected to be and the more certain we can be about this, and/or the more frequent extreme droughts will be, and/or the greater the risk of serious (effects of) drought will be. (And for really dark areas, these “and/or”s are really all “and”s.) In other words, the darker an area on the map, the more severe the expected (effects of) drought.

The maps used as source data are the following:

- Expected drought at 1.5°C and 2.0°C average global warming, and expected drought in 2030, 2045, and 2060 based on Park et al. (2018).2 (5 maps.)

- Changes in drought between 1971-2001 and 2021-2050 under RCP8.5, as well as the robustness and significance of the changes found, combined into a single map, based on Hugo Carrão et al. (2018).3

- Severity of drought and the frequency of extreme drought at 1.5°C, 2.0°C, and 3.0°C average global warming from Naumann et al. (2018).4 (6 maps.)

- “Drought risk” and “drought hazard” in the near future from Vogt et al. (2018).5 (2 maps.)

- Expected drought in 2071-2100 under RCP4.5 from Vogt et al. (2018). (This is obviously too far in the future, but projections for the end of the century under the RCP4.5 scenario will almost certainly be reached a few decades sooner, and can, therefore, be used in the present context.)

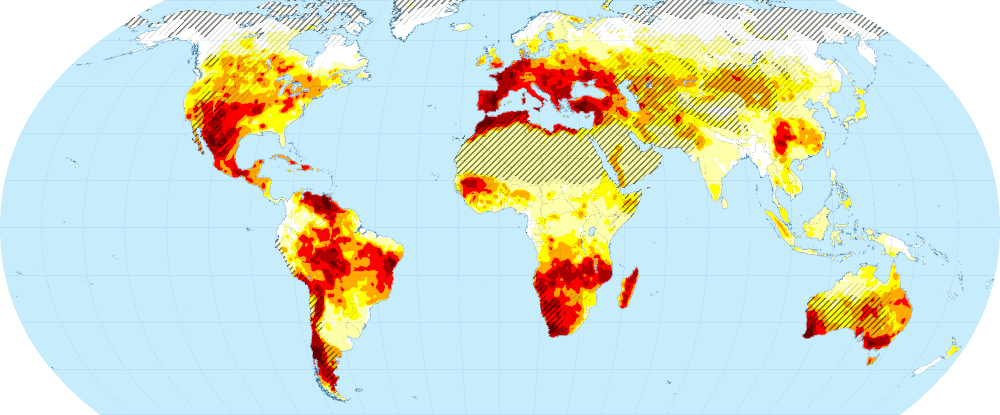

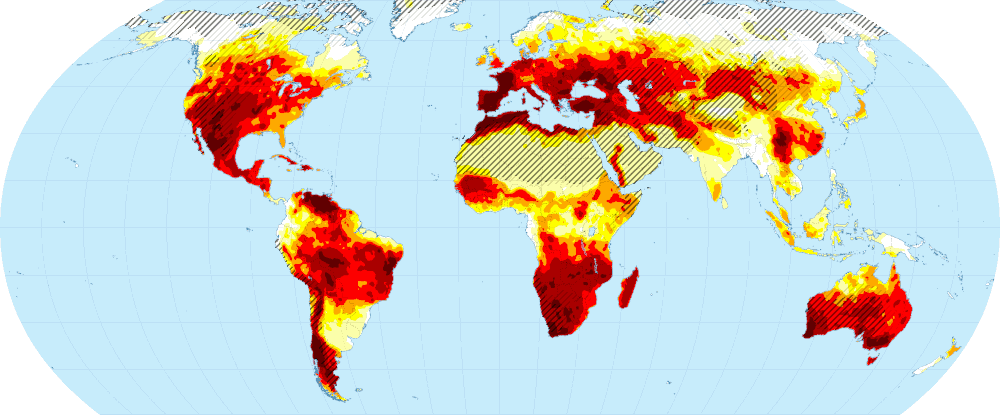

Subsets of these maps were weighted and projected on top of each other in accordance with their relevance to create maps of expected drought severity in 2030 (at approximately 1.5°C of average warming), 2045 (2.0°C), and 2060 (3.0°C).6 The last of these three maps is based on an assumption that emissions and global warming keep increasing in roughly the way they have been doing, and if there are reasons to believe that they won’t, then that map doesn’t represent a probable future. Furthermore, the further in the future we are trying to look, the less reliable the predictions, so the 2060 map should be taken with a spoonful of salt. Besides, in this article, only the 2030 and 2045 maps really matter, but I’m including the 2060 anyway to show where we might be headed. But let’s start with the map for 2030.

One thing I haven’t mentioned yet is that most of the source maps mask deserts and other areas that are extremely dry already. They do not all mask exactly the same areas, however, and not all of the maps used do this. For the combined maps this matters, because due to the way these maps are made, I could not distinguish these masked areas for which no data is available from areas for which no drought is expected. Consequently, the combined maps are unreliable (if not downright nonsensical) with regards to their predictions for already dry areas. To deal with that problem, I added dark and light gray shading to the map. Areas with dark gray shading are deserts, steppes, and other very dry areas; areas with light gray shading are relatively dry, but not as dry as deserts and so forth. Drought risk as shown in the map for these areas is relatively unreliable. However, these areas are (extremely) dry already so this matters little. In fact, I could just as well have colored them red.

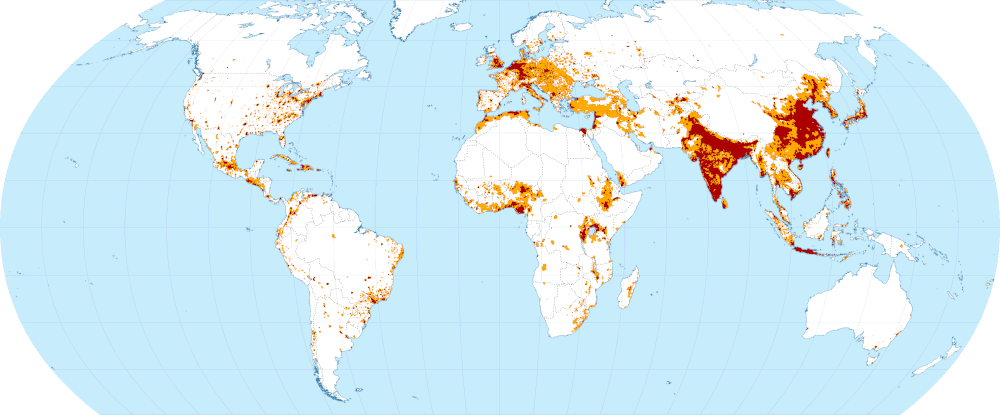

What the above map shows is – as explained above – some combined measure of the severity of drought, frequency of extreme drought, drought risk, and how certain we can be about our predictions. White areas are areas of no concern (at least in this respect); light yellow areas are of minor concern; and so forth. Orange, red, and dark red areas are – potentially – reason for worry on the other hand. How serious that worry should be depends on a number of things, including how well these areas are able to cope with the problem (which is largely a function of wealth and economic growth), and – most importantly, perhaps – their population density. If a densely populated areas experiences severe drought, that is obviously a much bigger problem than when an already sparsely populated area aridifies. Hence, in addition to drought maps, we need a population density map.

This map shows only two categories of population density to simplify things a bit and to help focus on what matters. Dark red areas are very densely populated with over 200 inhabitants per square kilometer. Orange areas are also densely populated with between 50 and 200 inhabitants per square kilometer. The rest of the world is – relatively! – sparsely populated. What this map reveals is where most people live: India and China together are home to more than a third of the world population. Almost no one lives in Australia, on the other hand, which is reason why that country can be mostly ignored.

Back to the drought maps. Here are the maps for 2045 and 2060, but as mentioned above, the 2060 map depends on assumptions that may turn out to be implausible and should, therefore, probably not be taken very seriously.

Below, I’ll look at these drought maps a bit more closely, but before doing that there’s at least one other general issue that needs some attention: refugees. In the first paragraph of this article I mentioned that drought is associated with water shortages, crop failures, famine, migration/refugees, and violent conflict, but causal relations in this respect are complex and there are very many intervening variables and other influences. That some particular area is expected to be hit by severe drought doesn’t necessarily imply that it will fall prey to violent conflict or produce an exodus of refugees – it merely significantly increases the odds of things like that happening. Unfortunately, we lack the kind of data to estimate those odds, so predictions in this respect will be vague, subjective, and very uncertain. Furthermore, there is no good way to estimate refugee flows either – both their numbers and paths depend very much on other factors and circumstances.

Nevertheless, we can make comparisons, of course, and learn something from those. The ongoing war in Syria is often mentioned as an example of a drought-related conflict. Regardless of how big the role of drought in causing it to erupt really was, the war lead to an immense number of refugees (over 13 million). About 60% of Syrians fled their homes. Of those refugees, half stayed within Syria, 40% fled to neighboring countries, and the remaining 10% fled to more distant countries.

There are a couple of very important things we can learn from these numbers. Firstly, the vast majority of refugees travel only relatively short distances. Long-distance refugees are rare. And consequently, refugee crises are – usually! – primarily regional problems. Secondly, regardless of how bad the situation gets, some people will stay behind. Perhaps, this will be even more important in climate-change-related disasters than in secondary disasters like war and other kinds of violent conflict. Fleeing war is dangerous, of course, even if staying behind might be more dangerous, but fleeing a famine might very well be impossible for the simple reason that one can’t flee on an empty stomach. Severe water shortages may not be the kinds of disasters one can run away from. The history of 20th century famines in Africa and elsewhere indeed suggests that those don’t produce massive refugee flows. In contrast, the slow undermining of the ability of a region to feed its people in case of a creeping kind of drought is quite likely to push people to try and find a way to feed themselves elsewhere, but in such circumstances fleeing is not urgent enough to produce the kind of massive refugee flows seen in Syria and other war-torn countries (instead, there will be a constant trickle). Whether a drought or other kind of climate-change-related disaster produces a significant refugee problem, then, is probably largely dependent on whether it causes the secondary disaster of violent conflict. That, of course, makes forecasting even more difficult.

South and East Asia

More than half of the world population lives in South and East Asia.7 Almost all of India and half of China are densely populated, and many other countries in the region are densely populated as well. Severe drought in this part of the world, then, may have far-reaching impacts. The maps below suggest that for much of the region drought may not be an existential threat in the near future, but what must be kept in mind is that we’re only looking at drought here – other types of climate-change-related disaster will have to wait until a future episode (or future episodes) in this series. Bangladesh, for example, isn’t threatened by drought, but by ocean level rise and an increase in the strength and frequency of tropical cyclones.

Focusing on drought and its immediate impacts, China is the biggest concern in this region. Thailand’s most populous area is also threatened by drought, but the scale of that problem is almost trivial compared to the huge, densely populated part of China that is threatened by drought. It is significant, however, that the most populous parts of China, which include its centers of political and economic power, are in the light yellow area in which drought is only a minor concern. For this reason, while drought may certainly be a destabilizing factor in China, it is probably not enough to bring the country down. In the contrary, if China isn’t hit by other major disasters, drought is probably a problem it can handle.

Africa

The most densely populated parts of Africa are much of Nigeria (205 million people; more if the coastal areas of adjacent countries is included), the area around Lake Victoria (approx. 180 million), and part of Ethiopia (115 million). However, although drought is a concern in northern Nigeria, these are (fortunately) not the parts of the continent that are most threatened by this kind of disaster. That dubious “honor” goes to almost all of southern Africa. (There is also a small part of West Africa that is threatened by drought, but that area is already very sparsely populated.)

The total population of this part of the continent is close to 200 million people. Given the severity of expected drought, it is unlikely that there will be enough water and food for that many people in the region by 2045 and possibly much earlier. Weather this will lead to major violent conflicts is hard to say. Some countries in the region have recent histories of violent conflict, which could easily flare up in circumstances of resource scarcity, but other parts of the region appear to be more peaceful. How many refugees Southern Africa is going to produce is, therefore, very hard to say. In case of Syria, mentioned above, the combination of drought and civil war (which may have been partially caused by drought) resulted in over 13 million refugees, 60% of the population. I don’t think we’ll see a similar percentage in Southern Africa, but when drought becomes severe (and it will become much more severe than it was in Syria) and violent conflicts do flare up (or start) it can easily reach 25% or even exceed that, and that would amount to 50 million refugees. Probably 90% of those will stay within the region or adjacent regions, but even that is a major problem, because almost the whole region will be hit by severe drought, and adjacent regions aren’t likely to be able to house and feed a sudden influx of refugees. Moreover, those adjacent regions include the aforementioned Lake Victoria region, which is already rather volatile (Rwanda and Uganda are part of that region, for example), and immigration of millions of refugees will almost certainly (further destabilize) that region.

Drought-related destabilization of Southern Africa could, therefore, create a domino effect spreading in northerly direction, first destabilizing the Lake Victoria region, then – with refugees spilling over to further adjacent areas – Ethiopia, Nigeria, and so forth. This would result in numbers of refugees exceeding 100 million or possibly even double that number (or more). But even without such gradual destabilization of the whole continent, if Southern Africa produces 50 million refugees, and the percentage of long-distance refugees is comparable to that in case of Syria, this would add some 5 million people trying to reach Europe, America, and other parts of the world (but Europe mainly), and that will also have a significant impact. (And of course, if a domino effect destabilizes the rest of Africa, this number will easily be doubled or tripled, or be even higher than that.)

Europe and the Mediterranean

After South and East Asia, Europe and the Mediterranean include the largest densely populated areas. Much of Germany and the Low Countries, as well as England, parts of Italy, and parts of the Mediterranean coast are extremely densely populated. Much of Europe and the Mediterranean are also within the zone that is most threatened by severe drought. Spain, southern Italy, and part of Turkey are slowly turning into deserts, and the narrow strip of fertile land along the northern coasts of Africa is getting narrower and narrower, slowly but significantly decreasing the number of mouths it can feed.

Much of Europe is rich, of course, and parts of it are even very rich, making it much easier for the continent to cope with the threat of drought, or at least with the direct effects thereof, but this isn’t equally true for all countries in the region. The economies of many southern European countries, for example, have been destroyed by austerity enforced by the EU – particularly, by rich northern member states such as Germany and the Netherlands. To what extent Spain and Italy, for example, really will be able to cope with severe drought remains to be seen.

Perhaps, the biggest concern for Europe isn’t drought itself, however – even though that is going to be a big problem as well – but its secondary effects. Turkey, the Middle East, and the densely populated northern coasts of Africa (i.e. the eastern and southern Mediterranean) are among the areas that will be most affected by drought, and many of these areas already have histories of (recent) violent conflict. It is, therefore, not at all unlikely that the eastern and southern Mediterranean will produce a whole bunch of “Syrias”.

Let’s look at some numbers. More than 90 million people live in the southwestern Mediterranean, and all three countries in that region (Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia) are subject to political and other tensions that could easily spark violent conflict in conditions of water and food scarcity. (It should be noted, by the way, that the drought projected for this area in the year 2030 is far more severe than the drought that may have indirectly triggered the Syrian civil war.) If this leads to 50% refugees (less than in case of Syria) then that creates a very significant refugee problem on Europe’s doorstep. Significantly, those refugees wouldn’t be able to flee to adjacent countries on the African continent because the Sahara is in the way and/or those adjacent countries would be in pretty much the same situation. Furthermore, Spain and Italy are more or less adjacent as well. Consequently, the percentage of refugees that would try to get into Europe would be significantly higher than the 10% long-distance refugees in case of Syria. But even if it would only be a little bit higher – let’s say, 15%, for example – then that would result in 7 million refugees trying to get into Europe (in addition to the 5 million refugees from Southern Africa mentioned above). Libya would add a few more (but not very many), but Egypt, on the other hand might remain more stable, unless a significant influx of refugees from other parts of Africa and/or the Middle East would destabilize that country as well. (And of course, the political situation in Egypt is hardly stable as it is.)

The Eastern Mediterranean is drying out as well, and all countries in that region also have serious political tensions or related problems. Nevertheless, I don’t really see the political situation in Western Turkey escalating into civil war. Lebanon, on the other hand, could easily return to its violent past, thereby exacerbating the refugee crisis in the region. Israel, on the other hand, is so heavily armed (by the US) that it can probably withstand any kind of uprising (and prevent refugee immigration). Hence, while the number of refugees in the region will probably increase, it is unlikely to reach more than double the present number and probably will stay below that. Of course, if Turkey falls prey to violent conflict (which isn’t impossible) this would radically change the situation. That would add many millions of refugees spilling into Greece and Bulgaria (which both will be affected by severe drought as well).

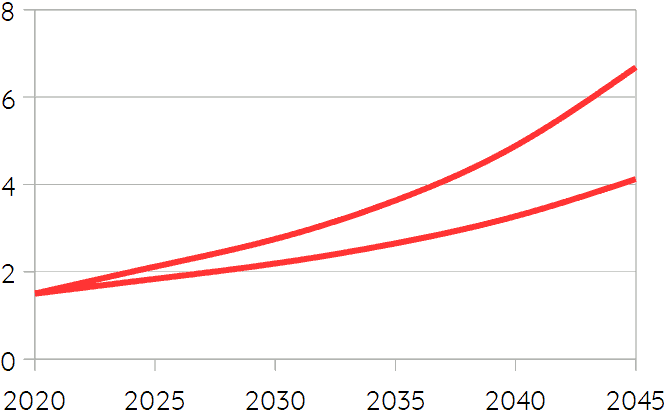

About one-and-a-half million refugees and other immigrants try to get into Europe each year. How would that change if some of the above numbers are added? Let’s assume that the various numbers of refugees are reached some time around 2045 (because the drought severity maps for that year are far worse than those for 2030) and that they gradually climb towards those numbers. In addition to the current influx, we’d have about 5 million from Southern Africa, 7 million from the southwestern Mediterranean, and additional million or so from the eastern Mediterranean, possibly many millions from Turkey, and probably many millions from West and East Africa when the Southern-African refugee crisis leads to destabilization of those regions. This gives a total number of between (roughly!) 20 and 50 million refugees. Furthermore, almost all of Africa is drying up, leading to an increase of the number of refugees from other parts of that continent as well, and given that the rest of the planet isn’t doing much better, refugee numbers from elsewhere are also likely to increase. The result looks something like the graph below (the lower line represents the 20 million scenario; the higher line the 50 million scenario), but don’t forget that these are very rough estimates (or guesses, really), and that other kinds of climate-change-related disaster (as well as economic issues) have not yet been taken into account.

What this graph suggests is that the number of refugees that tries to get into Europe will gradually increase. It will probably exceed 2 million a year by 2030 (and possibly sooner), and continue to grow faster and faster after that, reaching 3 or even 5 million per year by 2040, and 4 or even 7 million by 2045. (But again, these are very rough estimates. The exact numbers matter little, however. What matters – and what is a near certainty – is that there will be a very significant increase.) The EU will almost certainly respond to this by pouring more money into its militarized border force, Frontex, which will use increasingly aggressive tactics, effectively waging war against unarmed refugees. It’s unlikely that this will stop the influx, however, because the situation the refugees are fleeing will be (far) worse, and given the numbers, it is unlikely that any border force or fortification can stop them. Hence, southern countries like Spain, Italy, and Greece (as well as Bulgaria) will see massive increases in their refugee populations (while they’ll have to cope with their own drought-related problems as well), and recent history gives little reason to believe that there will be any kind of solidarity or aid from the richer, northern countries. Instead, the refugee crisis, together with direct effects of drought (and other climate-change related disasters), as well as the rise of nationalism, neo-fascism, and other forms of right-wing extremism (which are likely to gain force due to immigration, but also due to climate change itself8), will probably undermine the EU and any other kind of international cooperation. This is unlikely to lead to war in Europe (at least on this time scale, and with a possible exception for parts of the Balkan), but it will almost certainly frustrate efforts to reduce CO₂ emissions (and that is what matters most on longer time scales).

South America

Areas of greatest concern in South America are Venezuela and much of Brazil, but not the most densely populated parts in case of the latter. Rather, drying in South America will contribute to the change of the Amazon from rain forest into savanna, an irreversible process with severe consequences that has already been set in motion by massive deforestation. Loss of the Amazon rain forest will further increase global warming (but by how much exactly is not exactly clear9), but will also change climates and ecosystems throughout South America (and possibly even further away).

The drying of Venezuela could very well trigger violent conflict in that country, which is already facing political problems, partially due to US and European meddling. If Venezuela falls prey to civil war, there will be a significant flow of refugees to Columbia especially, and that country is also facing political problems of its own (such as increasing dissatisfaction with its right-wing government). A significant percentage of refugees will try to get into North America, the US particularly, adding to that country’s refugee problem.

North America

Much of the US is drying, leading to forest fires becoming harder to control by the year, but there are several other countries facing even bigger problems than the US. The most densely populated parts of Mexico and Central America are expected to face severe droughts, and much of the Caribbean is drying up as well (and facing increasingly frequent and increasingly strong hurricanes, moreover). Many of these areas are already plagued by violence (although criminal more often than political) and this is unlikely to improve much. In the contrary, increasing competition over scarce resources will make life in these regions increasingly difficult, leading to a significant increase of the number of refugees trying to reach the United States.

As in case of other refugee flows mentioned, its hard to give a realistic estimate of the number of refugees that will try to enter the US. The number of people affected by severe drought in 2045 in Central America (including Mexico) will exceed 150 million. Without violent conflict probably only a small percentage of those will flee, but even that would mean many millions of refugees. With violent conflict, the number of refugees trying to get into the US could easily reach tens of millions. The situation and its consequences are comparable in many respect to what I wrote about Europe above: border fortifications and violence will be used in a futile attempt to block the refugee flows;10 nationalism, neo-fascism, Trumpism, and other forms of right-wing authoritarianism will (further) rise; international cooperation will decline; and reducing CO₂ emissions will be de-prioritized or even forgotten.

Concluding Remarks

I can’t emphasize enough that the sketchy predictions in this article are very incomplete. The focus has been on drought here, and I have ignored the effects of heat, storms and other extreme weather, floods, and so forth. Adding these other effects of climate change, as well as the economic context (and whatever else matters), will be topics for further episodes in this series. The purpose thereof, however, is not so much to predict the near future itself, but to predict how much CO₂ we will emit in stage 1 of the anthropocene – that is, until net artificial emissions return to (near) zero – because that is what determines the mid- and long-term future of humanity and the rest of this planet. To know how hot it is likely to get (and what the likely effects thereof will be), we need to know how much CO₂ we are going to put into the atmosphere. That’s the main goal of this series.

There is, however, one conclusion that can be drawn from the foregoing: If we’d seriously want to limit CO₂ emissions, avoid civil wars and other societal collapses, and keep this planet as inhabitable as possible, we are going to need a massive refugee resettlement program. The refugee flows mentioned in the foregoing are pretty much unavoidable because near-future warming and consequent drying are already more or less locked in. To avoid that those refugee flows cause a cascade of collapsing societies, collapsing international cooperation, and collapsing CO₂ abatement, we need to make sure that people who can no longer live in their home regions due to the effects of climate change are relocated to areas that can still feed them (which will often be in the richest countries – forcing refugees to stay in the same region will amount to genocide if drought is what they are fleeing). Given the rise of nationalism and shortsighted neoliberal selfishness, it seems very unlikely that there will be such a refugee resettlement program. Rather, the dominant forces seem to have chosen collapse. The question is, how much CO₂ will we put in the air until collapse will put and end to that?

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog, 𝐹=𝑚𝑎, and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- With a possible exception for the hypothetical end of the AMOC, which might (equally hypothetically) plunge part of Europe into an ice age.

- Chang-Eui Park et al. (2018). “Keeping Global Warming within 1.5°C Constrains Emergence of Aridification”, Nature Climate Change 8: 70-4.

- Hugo Carrão, Gustavo Naumann, and Paulo Barbosa (2018). “Global Projections od Frought Hazard in a Warming Climate: A Prime for Disaster Risk Management”, Climate Dynamics 50: 2137-2155.

- Gustavo Naumann et al. (2018). “Global Changes in Drought Conditions under Different Levels of Warming”, Geophysical Research Letters 45: 3285-96.

- Jürgen Vogt et al. (2018). Drought Risk Assessment and Management – A Conceptual Framework (Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union).

- The global average temperature increases mentioned (in parentheses) are based on: Wangyang Xu, Veerabhadran Ramanathan, & David Victor (2018), “Global Warming Will Happen Faster than we Think”, Nature 564 (6 December 2018): 30-32.

- 54% according to the latest statistics. China and India together account for more than 36%.

- On the role of climate change in the rise of right-wing intolerance, see: Joshua Jackson et al. (2019), “Ecological and Cultural Factors Underlying the Global Distribution of Prejudice”, PLOS One 0221953.

- Steffen et al. suggest 0.05°C (0.03~0.11). See: Will Steffen et al. (2018). “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 115.33: 8252-8259.

- It will be futile because the number of refugees will just be too large.